2025

Acrylic, pigment and water-based ink with screenprint medium and paste on vinyl

200 x 360 cm (3-panels, each 200 x 120 cm)

2025

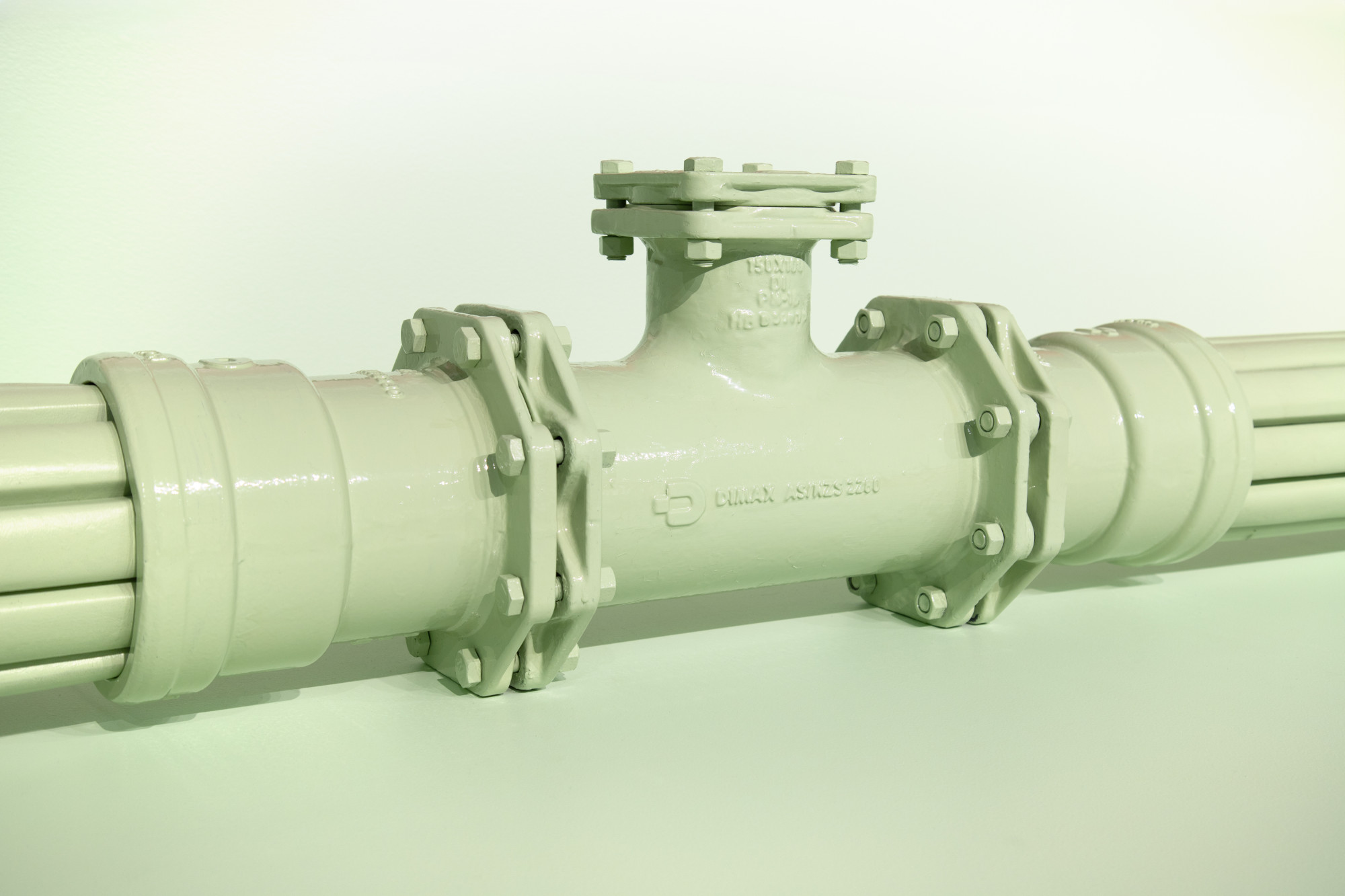

Acrylic, vinyl, polyurethane ‘open cell’ foam, ductile iron, pine, steel enamel

27 x 460 x 38 cm

2025

Acrylic with screen-print medium and paste on leatherette, pine, steel, enamel

100 x 650 x 120 cm

Photo: Warrnambool Art Gallery

2025

Acrylic, pigment and water-based ink with screen-print medium and paste on vinyl

180 x 260 cm (2-panels, each 180 x 130 cm)

Photo: Warrnambool Art Gallery

2025

Acrylic, pigment and water-based ink with screenprint medium and paste on leatherette, pine, steel, enamel

150 x 75 cm

Photo: Warrnambool Art Gallery

2025

Acrylic, pigment and water-based ink with screenprint medium and paste on leatherette, ductile iron, pine, steel, enamel, gas canisters

80 x 180 x 180 cm

The act of painting, in its enduring and often debated relevance, finds an impactful contemporary expression in the work of Alexandra Peters. Her expanded painting practice is situated within a lineage that critically engages with the medium’s history and its relationship to the surrounding world. Indeed, her work enters a rich dialogue with other key, often disparate, figures in art and theory. This exhibition brings together a body of work that navigates the complex terrain between manual gesture and the cool detachment of industrial processes, ultimately questioning the very nature of painting in our contemporary moment.

In Peters’ work there is a subtle but important presence of the artist’s hand, traces of personal touch and gesture that creates a strong tension with the way her marks are treated as objects or products. This ghostly presence contrasts with the impersonal, almost mechanical feel of the materials, highlighting the conflict between human expression and the commodification of artistic labour. While she employs methods of reproducing these gestures, aiming for a fingerprint-less surface1, the initial impulse of a work often stems from a manual action, a mark that is subsequently magnified, copied, and silkscreened onto vinyl. This process of initial creation followed by reproduction and erasure, mirrors a dual desire to both acknowledge and efface the artist’s subjective presence, poking at the romantic ideal of artistic expression while still embodying the act of painting itself.

Peters’ practice is clearly informed by a generation that came after the dominance of expressive abstraction. Like Michael Krebber, who stated, “I do not believe I can invent something new in art or painting because whatever I would want to invent already exists”2, Peters’ focus is more on a critical re-composition and interpretation of visual languages and materialities. Her engagement with industrial materials like vinyl, often associated with clinical sterility and mass production, is a gesture rich with implication. By replacing the traditionally permeable canvas with a non-absorbent ground, she introduces a material dynamic where resistance and opposition become central. Rather than aiming to produce a unified field, the gestures of painting are electrified by these tensions. They become expressions of difference rather than attempts at cohesion. Like in works by Michaela Eichwald, who also uses vinyl as a painting support, fluid gestures which suggest a fleshy, bodily presence are constrained, refined and denied by the non-porous surface, which threaten erasure through the always imminent possibility of simply wiping the surface clean.

The dynamic and disrupted forms within Peters’ work also find a compelling resonance with the practice of Steven Parrino, whose deconstructed canvases, often featuring tears, twists, and deliberate manipulations of the stretcher and surface, radically challenged the traditional integrity of the painting as a unified field. While Peters’ methods are different, the resulting visual impact shares a similar sense of fragmentation and a deliberate departure from regular painting structures. In this lineage of challenging the painted object’s conventions, Peters’ offers a contemporary analogue to Parrino’s aggressively altered canvases. Both artists rigorously question established boundaries and expectations, extending a historical trajectory that finds an early and powerful articulation in Lucio Fontana’s interventions into the canvas plane.

Another aspect of resistance in Peter’s works is their monumentality. They demand space, refusing an easy assimilation into domestic settings. This spatial assertiveness extends to the installation itself, becoming a crucial element in controlling the reading of the show, resonating with Cady Noland’s practice. Noland’s installations, often incorporating readymades and deliberately structuring the viewer’s movement through the space, aimed to create a specific psychological and critical encounter. Both artists set up a map of references, to establish an elusive yet demanding presence. The unseen violence that Peters’ work embodies, connects with an unsettling aura comparable to Noland’s practice. While Noland frequently incorporated overt symbols of American anxieties and potential violence – barricades, handcuffs, crime scene tape – Peters’ approach is more subtle, but even in the absence of explicit imagery, an undertone of aggression and societal unease often prevails.

Crucially, Peters’ use of elements like pipes can be read through the lens of Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s interpretation of “logistics.” In The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study3, Moten and Harney articulate logistics not merely as the science of efficient movement and organisation of goods, but as a fundamental structure of control and containment within capitalist and colonial systems. These pipelines, seemingly functional and aesthetically integrated into Peters’ installations, can be seen as material manifestations of these unseen networks of power. They evoke the arteries of global capitalism, the pathways through which resources and bodies are channelled and often controlled, mirroring the radical capitalism and colonialism associated with logistical networks.

The way these pipes are placed in the exhibition space, dictating the viewer’s movement and framing their perspective, further reinforces this connection to logistical control. Peters’ incorporation of these industrial conduits can be interpreted as a subtle yet potent commentary on the underlying structures that govern our movement and perception within the built environment and, by extension, within broader societal frameworks.

Furthermore, Peters’ dedication to the aesthetic possibilities of her chosen materials, even in their industrial nature, create a complex sensory experience, initially perhaps alluring but ultimately hinting at a deeper, potentially unsettling truth about the systems that underpin our seemingly ordered world.

Alexandra Peters’ work operates within a rich and critical dialogue with the history of painting. By embracing industrial materials, manipulating the artist’s hand through reproduction, and asserting a demanding presence in space, often articulated through the unsettling presence of logistical elements like pipes, Peters skilfully composes and interprets the enduring questions of paintings’ relevance in a world saturated with images and industrial processes. Her unsettling surfaces and carefully orchestrated installations invite us to reconsider the medium not just as a visual practice. Instead, her work functions as a critical lens through which to examine our relationship to materiality, space, and the often unseen networks of control that shape our contemporary experience. Alexandra Peters’ first institutional solo exhibition at the Warrnambool Art Gallery offers a compelling glimpse into an expanded painting practice that constantly challenges its own boundaries and our expectations of its decorum.

– Micky Schubert, Curator

End notes

1. Hughes, Helen, Mildura Atrocity Exhibition, Burchill/McCamley, Laura Burrow, Alexandra Peters, NAP Contemporary Art Gallery.

2. Birnbaum, Daniel, Kelsey John, Morgan Jessica, Man without Qualities: The Art of Michael Krebber, ArtForum, Vol.44, NO 2, October 2005.

3. Harney, Stefano, Moten, Fred, The Undercommons, Fugitive Planning & Black Study, Minor Compositions, Wivenhoe, New York, Port Watson, 2013.

~

Originally published for the exhibition The Graven Image by Alexandra Peters, presented by the Warrnambool Art Gallery from 2 August – 19 October 2025. © The authors, artists and Warrnambool Art Gallery, 2025.