Nick Collerson reads from Plato’s Republic.

NC: I’ve been doing some translations of chapter six from Plato’s Republic (see endnote). They are talking about speaking, and what’s happening in speaking. Like the whole text, it is full of puns, or double speech of Greek philosophical writing. For example, the word “chance” is mentioned, which means Hermes, and the word for necessity, “Ananke”, also means the Goddess of necessity. She’s symbolised with a thimble and thread, and she stitches the logos together. The whole logos is stringing together contradictions and sounds of words in a row as the prayer of serpent or two.

MG: Whilst you were reading that to me, you took a few asides and used words like completeness, inevitability, and necessity, alongside words like conjuror and duality — what do you mean by completeness?

My idea of completeness comes from meditation… and this is also the reason I read Plato, Aristotle and any of the Greek philosophers differently. I started meditating in my early 20s, I’m in my 40s now, so it’s been a long time. I treated meditation as a serious subject with a curriculum, I read books, met monks, did some retreats, listened to what people said. I spent a lot of time doing it, very earnestly. And certain things happen, certain experiences happen. And so that opens up a different sense of experience, which I guess you’d say, is aesthetic or perceptual experience. It opens up a flow state, which is just what happened in my experience. All my sense doors opened up as a fluid flow. And because it’s joined in a sequence, like a river, the beginning of the river is the end of the river. Something changed about perception then, and with it the idea of completeness and what perception is, and how it integrates with painting and observation and even music.

That change happened when I was in Chicago meditating a lot. I would meditate for maybe eight to ten hours a day, waking up very early and just going at it. During a break I sat down on the couch near an air conditioner roaring loudly, then automatically, accidentally, my senses just opened up and the hearing was just the sound of the air conditioner rushing with no position. Hearing immediately fell away in time and arrived again as the same flowing sound… it was fluid, devoid of conceptual abstraction breaking up “this moment” from “that moment”, and all my sense doors opened.

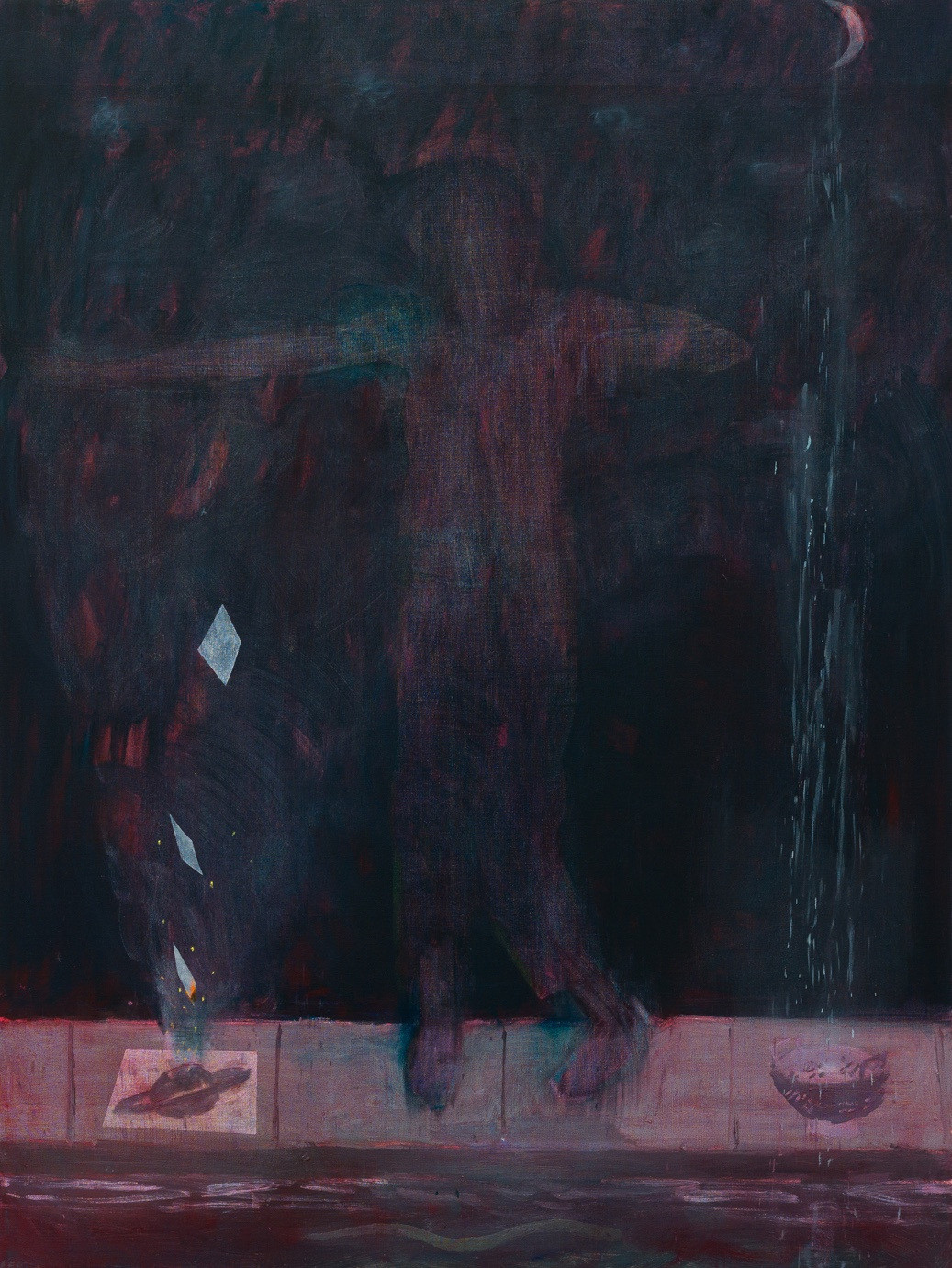

2025

oil on canvas

167 x 183 cm / 65 3/4 x 72 in.

Photo: Josh Raymond

When did painting start for you?

It’s been a series of questions. How do you draw something? I was drawn to it instinctively. My parents supported me; I’d walk to my painting teacher’s house after school in Brisbane. His name was Arthur Xavier — half Portuguese, half Chinese — at his framing workshop under his house he’d teach the fundamentals of drawing. So I learned about shading and handling oil paint and a bit of mixing. That pushed the ability to engage with looking and making, the idea of modelling something or shading something… Actually, I should phrase it this way, when I learned how to shade and see shade it was like a light went on, the world of light and shadow, my seeing became more attentive. And that’s one part of art making, the perceptual aesthetic engagement. That is also like the influence of Eastern thinking on art making.

After school I went to Queensland College of Art but dropped out — it wasn’t right for me. I always made work independently: painting, sculpture, music. My practice was self-driven.

You made the decision to leave Queensland College of Art — what else was happening then?

I was in my early twenties, skateboarding a lot, fully immersed in that at the time. But I always thought of myself as being an artist of sorts. I just intuitively thought that was how I was doing things, how I think about things. It’s not uncommon for skateboarders to think about themselves as artists as well. Mark Gonzalez is an artist — most skateboarders would say he’s primarily an artistic skateboarder. I also went to India in 1999 with a friend — driven by curiosity — but it was transformative. The density of time there, aeons layered together, changed how I saw things. That led to yoga and meditation, prior to the experience I had in Chicago.

In Brisbane I began painting urban scenes in my garage, not thinking at all about having a gallery or a career, just: what is a painting? I loved Beckett — the absurdity of Waiting for Godot, the weirdness of a single motif, like the tree in Waiting for Godot, which is just like a poetic marker for the actors’ absurd dialogue and their dance around it…

I was also working at a Bonsai tree nursery at the time; I encountered the very rigorous classification of the aesthetic forms in bonsai tree composition. Those experiences — composition, absurdity, meditation — merged naturally. I developed my painting aesthetically based on this meeting of contemplation and aesthetics. I would do my own research on early modern painters just to get a sense of how these artists were thinking. Some of my earliest readings into art history were on Piet Mondrian. I wasn’t so concerned with the analysis of historians. I really wanted to find evidence of what the artist was thinking about. So Mondrian was interesting — he was into theosophy. At the time I was like, what’s that? You know, what is that? I had no idea what that was. And then I read Miró’s letters and that was extremely eye-opening. Juan Miró is someone I adore as a painter, but seeing his attitude to culture and his attitude to his contemporaries and particularly the French symbolist poets — that’s the first taste I got of the link between poetry and painting in modern art, which just became an all-consuming subject for me.

Look at Mondrian when he was a very young painter. You look at those early works and you think, oh, the clunkiness, or the problems with perspective. These become a complete revelation when you know who Mondrian becomes. You said to me “instinctively, I just knew I was a painter. I was calibrated as a painter”. And when you talk about Mondrian, I see that instinct in the way he treated perspective with that awkwardness. It became a superpower in a way, or an early rehearsal for what was to come. After that it’s a matter of finding a language around it.

c.1900

Collection Tate, London

The thing that was fascinating about Mondrian is the choice he made in the pursuit of his abstractions. Why would someone do this? Why would they paint themselves into a corner? Why would someone go to this extreme? It’s like he started playing with haiku poems, a limited vocabulary. Every time I encounter an artist who does something very particular with vocabulary, I want to find out what they were thinking about. Not what the effects were, or how they fit with the common reading of European painting as beginning with imitation then to abstraction, and then blah, blah, blah, installation or wherever we are now. But just the specific choices of specific painters and what they were concerned with. I wasn’t interested in Abstraction’s historical trajectory, but the poetic logic behind decisions. Same with Miró, he’s fascinating. Why did he make these choices? He’s aware of Paul Klee, and he was ripping him off a little bit. And there’s Marcel Duchamp, another one who’s just a question mark — what the hell is he doing? Why is he doing this? Where’s he from? I don’t try to think about how they should inform what I’m doing formally. Like, oh, I should be doing readymades. No, I think about the poetic game they’re playing, it’s a linguistic thing, and this gets to the point that I want to make about mark making. It gets back to the question you’re asking about instinctively being a mark maker. So my idea of being a painter is not really a material thing. I think of painting as being poetic. It’s an extension of writing. My game isn’t about an innovation of material qualities. So with painting, as an extension of writing, I play with images. Yet it’s more like archetypes of images and a linguistic move. I do not paint imitative inventories of appearances. I’m kind of aiming at a psychological space or a contemplated space. So, in that way, it’s more like a poem…

I think there’s a musical tone to your painting as well. I remember first seeing your paintings nearly 20 years ago now. I felt that then. I didn’t know what the score was that underpinned or ran through those works, but I felt that they were both lyrical and musical. You said dithyrambic poetry is like a spiritual opera. They are communal and choral. The works you’ve made over the past few years feel more operatic — characters, tonality, drama.

Yeah. I certainly think the last two shows we’ve done together have been more focussed in their play of meaning. Previously I was happy to work in a way that’s very chaotic, like, not even knowing how it’s gonna hit. I trust the process that much. It’s not to say I show everything, but I’m happy I have done shows with a very kaleidoscopic and absurd quality. I don’t mind it being a whirlwind like a storm coming through. I mean, that’s part of the dithyramb too. That’s the storm’s breath smashing a tree. This is the metaphor of the body, the body of nature, or the body of our reality we perceive as being apparently scattered and that we have to make sense of, complete it in some way when we’re in this life faced with so many things, where am I, who am I? That’s the puzzle or the mystery.

2024

Oil on canvas

183 x 244 cm / 72 x 96 in.

Photo: Josh Raymond

So completeness consists of both multiplicities and sequences of singularities?

Well, multiplicity or singularity comes down to the idea of dualism and non-dualism. There’s a great line from the brilliant 13th century Japanese monk Dogen. He said, “to study the self is to forget the self, to forget the self is to be enlightened by the 10,000 things”. In Buddhism the phrase “10,000 things” stands for myriad things. It’s multiplicity coming to bear on experience which in turn affirms the wisdom of oneness, not as quantifiable discursive thought, but as the same accent in all different thoughts and feelings, even in an apparently wrong word or contradiction.

Would you say contradiction isn’t just acceptable, but a necessity?

Yes, and it’s not a problem. Philosophers have ways of talking about it — from Heraclitus through to the playwrights, who were artistic philosophers, they’re really writing dithyrambs as plays. Plato wrote dithyrambs as dialogues. Aristotle wrote prose poems with a dithyrambic quality influenced by his own understanding. All the dithyrambic poets write in the same spirit, just as Buddhist writers are influenced by Sunyata. Dithyrambs unite things together, like in Aristotle’s Peri Hermeneias, usually translated as On Interpretation. Peri means “around”, interpretation means “Hermes”. It’s the unifying dithyrambic ritual of the dance circling around the idea of the Hermes stone. He describes words twisting together like twine as the “dual vipers” on Hermes’ wand, and he binds contradiction, negation and affirmation to one another, touching in a line like the “staff”.

In the text, you can see the structure, like it’s a drawing, like a painting written in words. So that’s how contradiction is handled in philosophy, all argumentation and polarised opinions merely symbolise conjectures held onto, competing conjectures carried by Hermes, who is the movement of mind accompanying all positions. Insofar as you think anything, your mind moves, Hermetic activity is happening. So Sunyata is the Platonic Idea Hermes, the formlessness of experience that is truer than opinions. See, even if I lie to you, if I say something to you like “the world is flat”. Well, you know it’s incorrect. But it’s true that you heard something, so the movement of mind is true, it is always truer than information.

Completeness isn’t didactic. It’s not about a quantifiable concept, meaning or persuading someone of a story. Hermetic work doesn’t tell you a particular thing, it engenders an experience.

That’s what happens in European poetics too. Shakespeare writes, “One thing expressing, leaves out difference. Fair, kind and true is all my argument; fair, kind and true, varying to other words, and then this change is my invention spent.” That change itself engenders the “fair, kind, and true”. Nothing ever really misses the target. Aristotle writes, “…movements of every kind are hitting mark on the same objects of contemplation, they are always hitting the mark on these here just like a few just now are cutting things into pieces [aka. Dionysus]: and truly just as they say many would throw a striking hit, at another time you will throw another sort, and he is coming together in agreement upon the surface of these here.”

Removing the element of failure?

I mean that is getting into more of an idiosyncratic or pragmatic thinking about the process of painting. I like courting failure, trying difficult things to see how far I can go. I’ve used variations and repetitions… People might see repetition in my work now (the recurring sidewalk motif) but that’s deliberate. It’s a path that continues while everything else varies.

For years I painted anything as a subject; abstract, figurative, portraits, whatever. I had this phrase for myself, ‘painting, painting’ — a circular idea. That idea predates my Greek studies. In Buddhism, philosophical insight comes through “the ten thousand things”. I thought, painting isn’t of something — the universe itself is painting. Like the myth of Shiva’s dance of the cosmos. For a dancer, it’s dance; for a musician, it’s music; for a painter, the universe is paint, unfolding pigment before our eyes. Painting is not a material object, it’s a process of interpretation. That is an intellectual event. I didn’t want a particular style. It was contemplation. Over time inquiry led to pataphysics and the tradition it is part of — a trail of breadcrumbs.

You could take that trail back endlessly, but in regard to your own practice, when I saw your painting Kora, you said to me that it is also your painting Dionysus, and Dance. It is the same painting. Is that revisiting or a metamorphosis?

Both. I’m unashamedly using motifs from tradition. Modernism is often thought of as a break from tradition to generate newness, newness, newness. I don’t think it’s exclusively that because you can see the use of the older motifs in the surrealist, Max Ernst and Duchamp, Dali, Hilda Doolittle. — they refer to mythological ideas and used them astutely. I like to pay homage to that, so I’m putting out bread crumbs so people can make connections.

2023

Oil on canvas

183 x 137 cm / 72 x 54 in.

Kora connects to Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher. The name Madeleine — from the German “girl”, is kora, maiden in Greek. Kora is Persephone, queen of the underworld, equivalent to Kali. Poe’s title itself — the fall of the beginning — is circular, an ouroboros, the cycle of Persephone’s murderously fertile life.

So Kora, Dionysus’ body forming, and Dance — they’re part of the same pantheon, morphing in time and contemplation.

2024

Oil on canvas

183 x 137 cm / 72 x 54 in.

Photo: Josh Raymond

2025

Oil on canvas

183 x 153 cm / 72 x 60 in.

Photo: Josh Raymond

Improvisation seems essential too. I don’t just know you as a painter but a reader, writer, and then there are other physical elements of you as a drummer, also you as a skateboarder. These last two offer a physical act of interpretation. Does that give you freedom?

Yeah. I love the interpretive process. Playing drums is opening to the unfolding of listening, paying attention. Improvisation isn’t wilful chaos, it’s concentration and instinctive response.

Skateboarding’s beautiful — an open-source code of tricks that people contribute to and interpret differently. It is creatively moving through the environment. The easier you move through something difficult, the more it looks like nothing happened. That’s how they describe someone as having a flowy style.

I like to paint that way — as if nothing’s happening. Maybe it doesn’t seem so sophisticated, but maybe there is more there than meets the eye.

It’s informed by more than it reveals.

Yes. Western culture often treats art as information to decode. There is not as much attention to the innate parts of ourselves. We think it’s about something we must “get,” reading the wall text, categorising.

But the strength of art — music, dance, painting — is participation. Theoria in Greek means being a spectator and contemplator; it also meant sending an envoy to an oracle. It’s contemplation as experience.

Paintings open slowly. There’s no burden to think anything profound. If you understand red for example, that’s enough.

Photo: Josh Raymond

I never feel bookended by your paintings. I feel that it (the painting) has kept enough from me, or out of sight, to convince me there’s a reverberation of that painting that might come back in a different way. It has the potential to resurface or come through in another painting. So I never feel like a painting is being closed off.

Yes. Dithyrambic texts are incomplete, completion is with the spectator. A painting should grow in the viewer. The incompleteness is instinctive, like perception flowing freely. Aristotle’s writings were said to be incomplete until the intellectual organ of the reader sharpens itself. That’s what I want, paintings that keep thinking. Aristotle, the peripatetic philosopher, was said to have written with rhythm, not verse; meaning unfolds in rhythm.

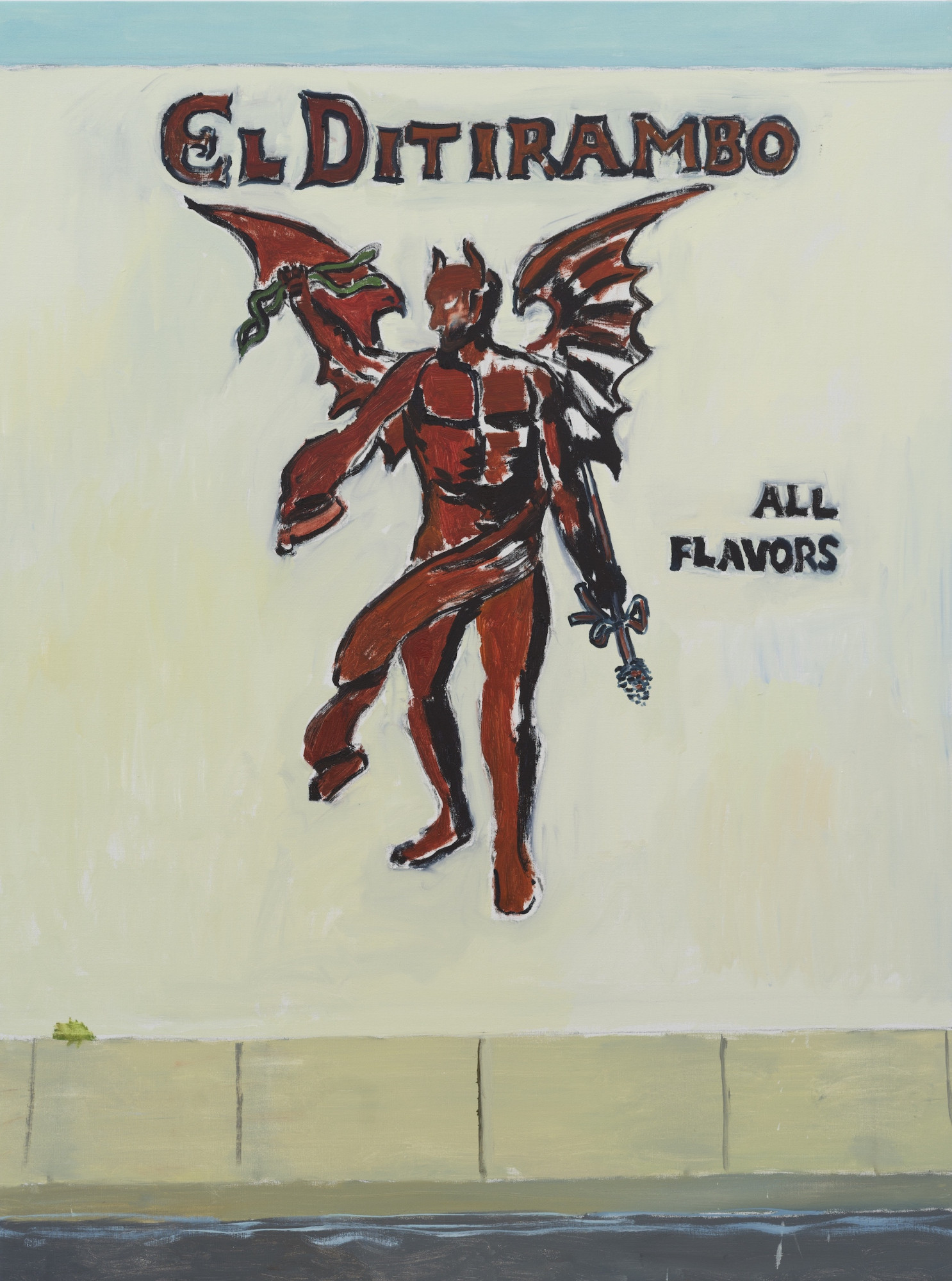

And rhythm can be fast or slow. We were talking in your studio one day about your painting El Ditirambo. That painting came quickly. It was charcoal, it was painted over and finished, then three or four days later you came back and added a tuft of grass, but that was it. The formulation of that was instinctive. I like that in contrast to paintings that have gestated for years and that you’ve chosen to go back in. You haven’t wiped them clean but rather vanished part of them before moving back in.

I’m happy to work in every way, a painting that’s very quick or a painting that takes years. That painting did come very quickly, others take time.

2025

Oil on canvas

183 x 153 cm / 60 x 72 in.

Photo: Josh Raymond

And time — Chronos in the making of work?

Yes, Saturn appears often, I place those symbols deliberately because I feel it is important to make the tradition visible.

I see those symbols as your working notes. You’ve put them into the painting to solve a riddle rather than putting a riddle into a painting. I feel there is a generosity in that. You are sharing your working notes within the painting.

Yeah. Like Jung’s Red Book, they’re meditations. Not that I’m necessarily Jungian, but I appreciate he’s done something pretty special in his artistic and poetic contemplative pursuit. But yeah, these are my own notes. But I’m in two minds, because on one side they are personal, I’m thinking through making, and feel like I’ve lived my life correctly if I’ve made a painting. That’s just the irrational part of being a painter, irrespective of whether a painting is seen or sells or not. Then the other part is that I like to share an overlooked part of the tradition of art. I’m as much a spectator as a maker. Sometimes I spend more time looking — as I did with Buddhism, Chinese poetry and painting. Now it’s the dithyrambic poetry of Plato, Aristotle and others. But the irony of dithyrambs is that though they overflow with words, they are in fact a long laconic pun or epithet — it is very playful, I can’t help but share it.

So it circles back to play.

Yes, always play. The Greek word aporia means “no passage”, but in a dithyramb it is not blocked, but endless. You can enter but you can’t pass through because it’s never ending. So it goes on and on.

You can’t enter with the expectation of coming out the other side.

Not being able to pass through means it isn’t a race, wisdom shouldn’t be competitive. I think there’s a kindness that comes through in ancient philosophical writings. After all philosophy is about the love of wisdom, so love and kindness should be central. Encountering an aporia can be helpful. Many years ago (just after leaving the College of Art) I remember sitting on a balcony painting outdoors and suddenly asking myself, what am I painting? What is the subject? That question stopped me. I began turning inward, thinking about perception itself. Paying attention became the subject. I think that’s when I really noticed empty spaces, a set of stairs, a pair of kid’s shoes in a hallway, or a chair — mundane things.

They are authentic moments — the lack of stimulation in those nothing spaces lets you enjoy the mundane or the ordinary.

Exactly. Any object can be a catalyst for attention — like Van Gogh’s peasant shoes. To really look is peace. The earliest relief carvings of the Buddha were of two things: the bottom of his feet, meaning to walk the path, and the second was an empty seat. Just an empty seat, no icon. It is beautifully poetic that an empty seat stood for the Buddha. When I paint something with empty space, it’s a space for someone else as well. It is like opening a door.

Openness can be lacking in the West. There is a presumption of knowing the whole narrative. This leads to trauma that closes people off to each other and themselves; fight-or-flight responses make us defensive. Collective trauma shuts down openness.

Art can open it again. It has a divine or contemplative quality — not religious, but human. Plato and Aristotle call the divine that is shared by all “common”, an epithet of Hermes.

2025

oil on canvas

167.5 x 183 cm / 66 x 72 in.

Photo: Josh Raymond

Do those divine things require us to suspend ourselves — to realise there are things that operate outside of what we can comprehend neatly?

It’s not about suspension, because it’s not volitional. Hermes constant formlessness accompanies thought and language. It isn’t about relinquishing our humanness, it’s realizing that we are held by what we share in common.

In this information age we are lost in the sea of vying positions and arguments. The West has its ideologies, which are about information, about discrimination, about which creed or which ideology you want to identify yourself with. What’s suppressed is Hermetic thinking — not a position, some amount of information, but an accent of the experience of all thought, an idea with infinite names.

I’m using this as a metaphor for the Greek philosophers again, but a Buddhist master hears the formlessness in anything. Their wisdom is unrelenting, and so it is for philosophers too.

The experience of being alive is walking down the street, or walking in the agora, which is the place of assembly.

The sidewalk?

The sidewalk motif in my paintings came naturally. Some are in the light and some in the shadows. That’s also an authentic, emotional thing. I’m not trying to be clever, it’s actually how I feel. Sadness, or whatever feeling it might be, should be free to be carried into the painting. The dithyramb is the genre that includes all genres. Tragedy, comedy, the epic, which is the heroic or epic tale of our life. Tragedy and comedy and puerile sex jokes which characterize the satiric verse. It is all these, even fart jokes, everything, blah blah blah, the dithyramb has everything. I mean, the sex jokes are ridiculous. I won’t go into that, it’s wild.

That’s the challenge. To keep everything and anything open, and not to shut off the possibility of in your painting.

Yeah, that’s like Dogen, the idea of the 10,000 things — everything as the universe. The dithyramb parodies separation. Even opposition contributes to oneness. My position is everything is one, it’s all the universe. But then someone might say, “ha ha, but what about this?” I’m like, what? Did you miraculously step outside the universe somehow to make that point? No, you’re a part of it too. That is the irony of dithyrambic poetry, everybody is in this song.

Photo: Josh Raymond

I like that. If you can’t step outside of the universe and look at it objectively, you can’t create the hierarchy yourself, right?

Yes. In Greek, hen (ἕν) means One, but also flow and speech — the ‘One’ fractures into multiplicity yet expresses a unity of flowing speech. That is very different from our understanding of One in English. The word “rhetoric’s” root means flow of water; and is also related to the root word εἴρω, meaning “to speak” and also “to stitch together in a row”. Aristotle opens On Interpretation with the middle/passive voice of εἴρω, Eritai (εἴρηται) — meaning “it is said,” but as a poetic pun in the middle subjunctive voice it is self-referential demanding speech, so it means — “he demands to speak of himself-stringing together in a row”. This pun is appropriate for a non-dialistic text on the Hermetic reality of speech and thought called logos. Indeed the word “interpretation” in the title is etymologically from Hermes the flowing-interpreter archetype.

I think of the water that flows through the drains and the sidewalks of your paintings. The action of watching something flow is that it’s constant, but it’s also reactive and deviant. It moves around and through things and it doubles back on itself. Flow doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s without resistance, it just means that it continues to move.

Yes. In change there’s constancy if everything is shifting. Heraclitus’ paradox — “changing is at rest…” therefore always the same. Philosophers suspend discriminative thinking by collaging all thought together, like a sphynx, to reveal another idea — a “common” emblem of the flow of thought. This is non-negotiable. This is the checkmate of the flowing Hermetic accent of philosophical thought. Like Buddhism it is not an argument, it’s engendering a common experience.

Western thought prizes argument and persuasion. We’re forced to identify something, separate out, argue it, and build a wall around it, and be upset if someone disagrees with us. Hermetic thought invites the experience of differing interpretations, like musical variations in jazz music. Aristotle wrote, “it is necessary whenever any name is contradicting anything seeming to be an omen, to meditate [ἐπισκοπεῖν] upon how many ways this omen could have been given by that which has been spoken-stringing together in a row [εἰρημένῳ]… The omen is reality itself — the flow of the logos. The logos is not a verb, it is a noun, or a verbal-noun, meaning speech, gathering, reckoning… You can’t deny it, yet even if you do, there it is.

From book 6 of Plato’s Republic

Socrates says,

Certainly the grace is from these here, I then said, and we are seeing this before our eyes just now and nevertheless we have been speaking of dreaded things, these have been forced underneath because of the-unconcealed truth, because it is not becoming complete in the same way at any time/drunk [pun] neither as the city nor the government nor indeed a man, until by few things such as those by the philosophers and not by oppressive toils, but by these having now summoned unrealized oracles, by necessity/goddess of necessity with a spindly of thread [pun] it surrounds someone from out of chance/Hermes [pun], whether they are willing or not, to take care of the city, and these are eavesdropping on things happening in the city, or now to the lords or to sons that are in the basileia-queens/Basilisk-serpents [pun] or love/I will speak-stringing together in a row/pouring forth/when [pun] that fell upon them from anything of the gods inspiration agreeable to the truth of philosophy .

But then and there it is like it is impossible for whichever of two/drunk-monstrous serpents [pun] of these things to happen or both of those two/monstrous serpents [pun], indeed I at least am saying logos-speech is not at all to be a possession/it is a tutor deity [ἔχειν, pun].

Therefore in this way we would be laughing righteously in observance of custom/on a sacred serpent [pun] like otherwise speaking things in resemblance to prayers. Or is it not in this way?